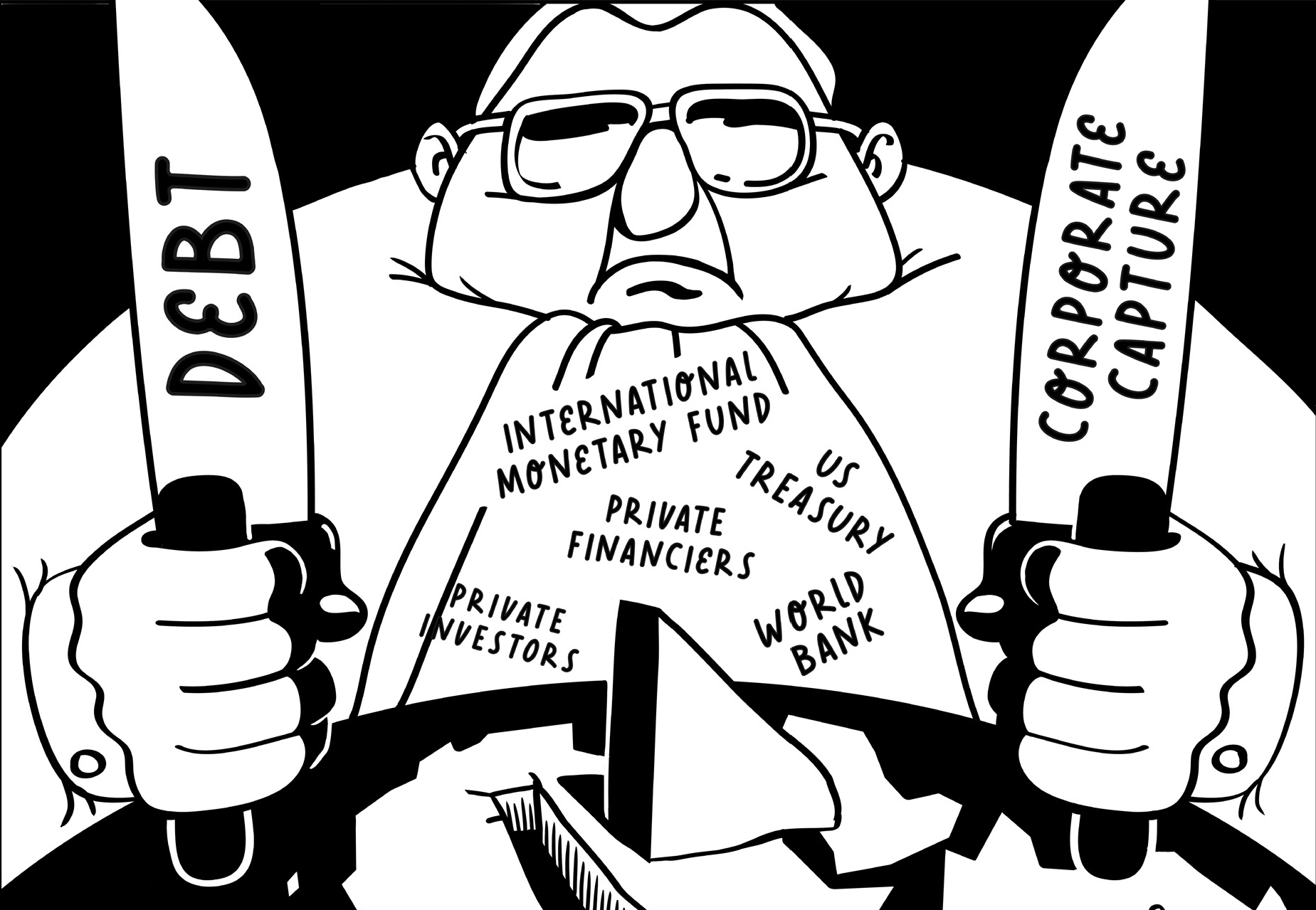

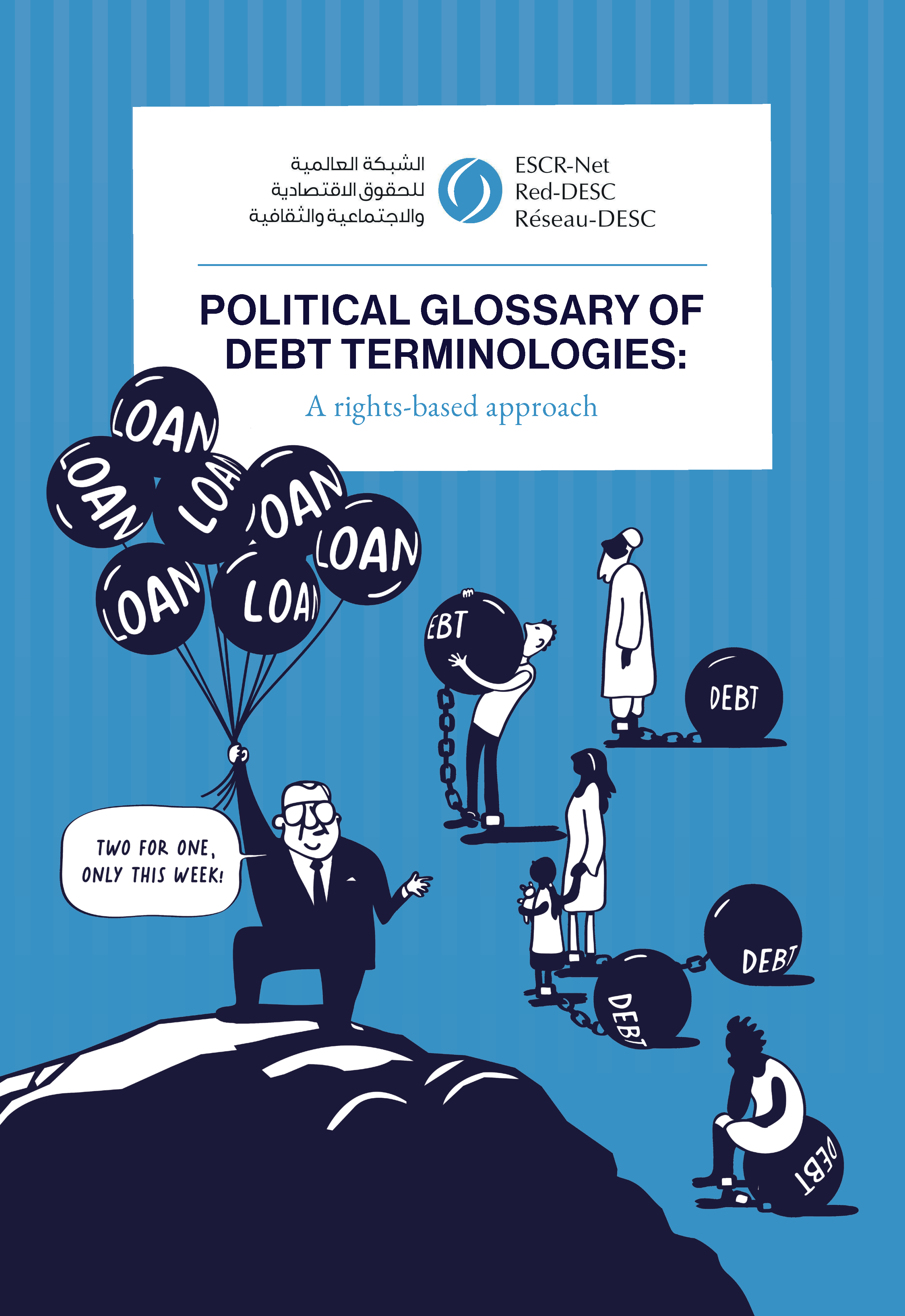

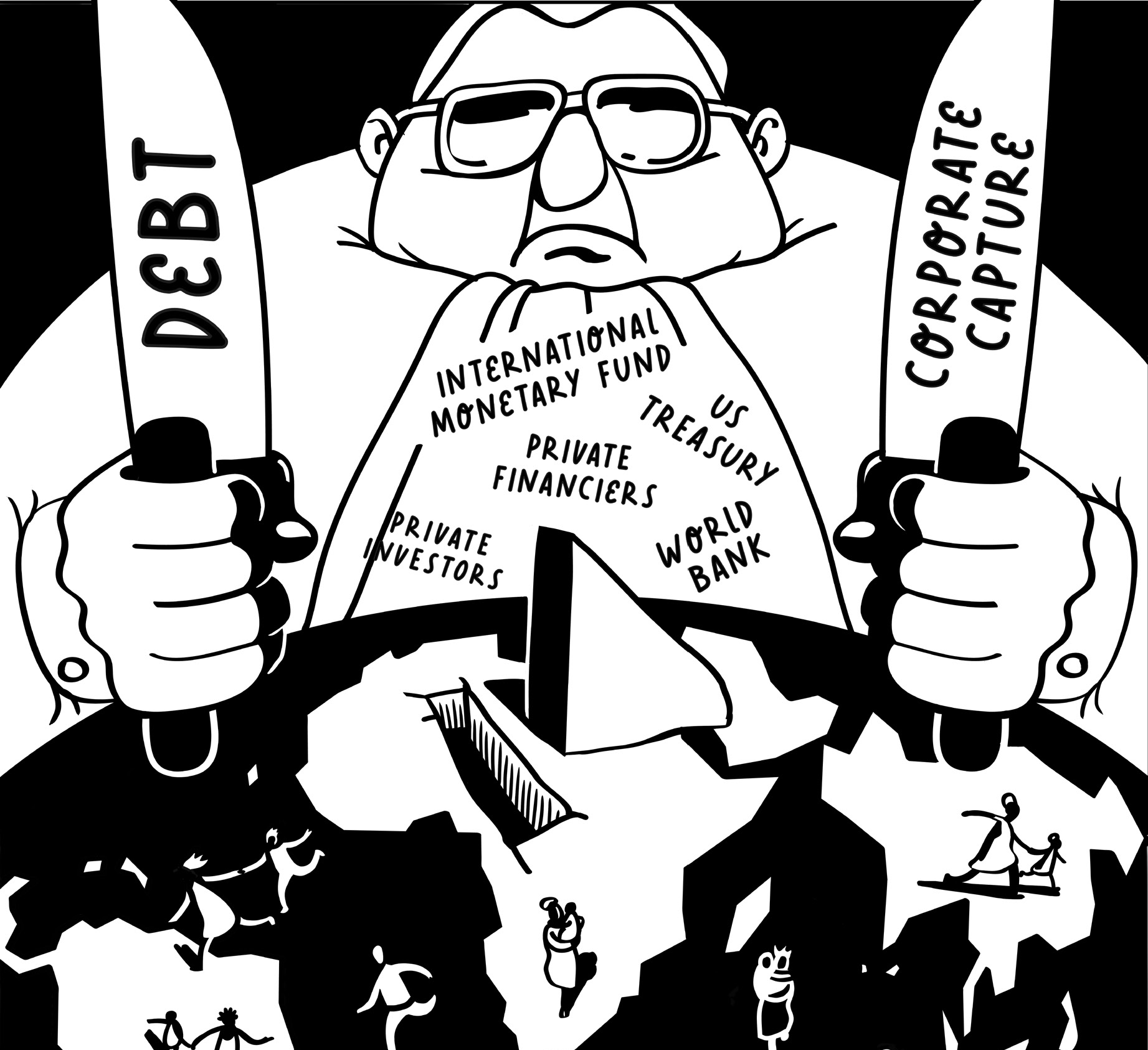

Debt is a manifestation of neoliberal capitalism and its crises. The current waves of debt accumulation have been an increasingly central phenomenon of the global economy since the 19th Century with the development of sovereign debt as a powerful tool for colonial empire-building. This led to the expansion of capital markets by creditors from industrialized countries who saw an opportunity to invest heavily abroad for profits. The influx of foreign capital dangerously inflated the debt of occupied and impoverished countries, bringing them closer to insolvency. Despite successful anti-colonial struggles, former colonies have continued to face debt legacies that they inherited from colonial regimes, as well as ongoing economic imperialism. This was further intensified in the 1990s, following the rise of the US as the dominant global superpower and the related imposition of the neoliberal Washington Consensus. The term ‘Washington Consensus’ refers to the agreement between the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank and the US Department of Treasury on new economic policy recommendations shaped by corporate and financial elites.

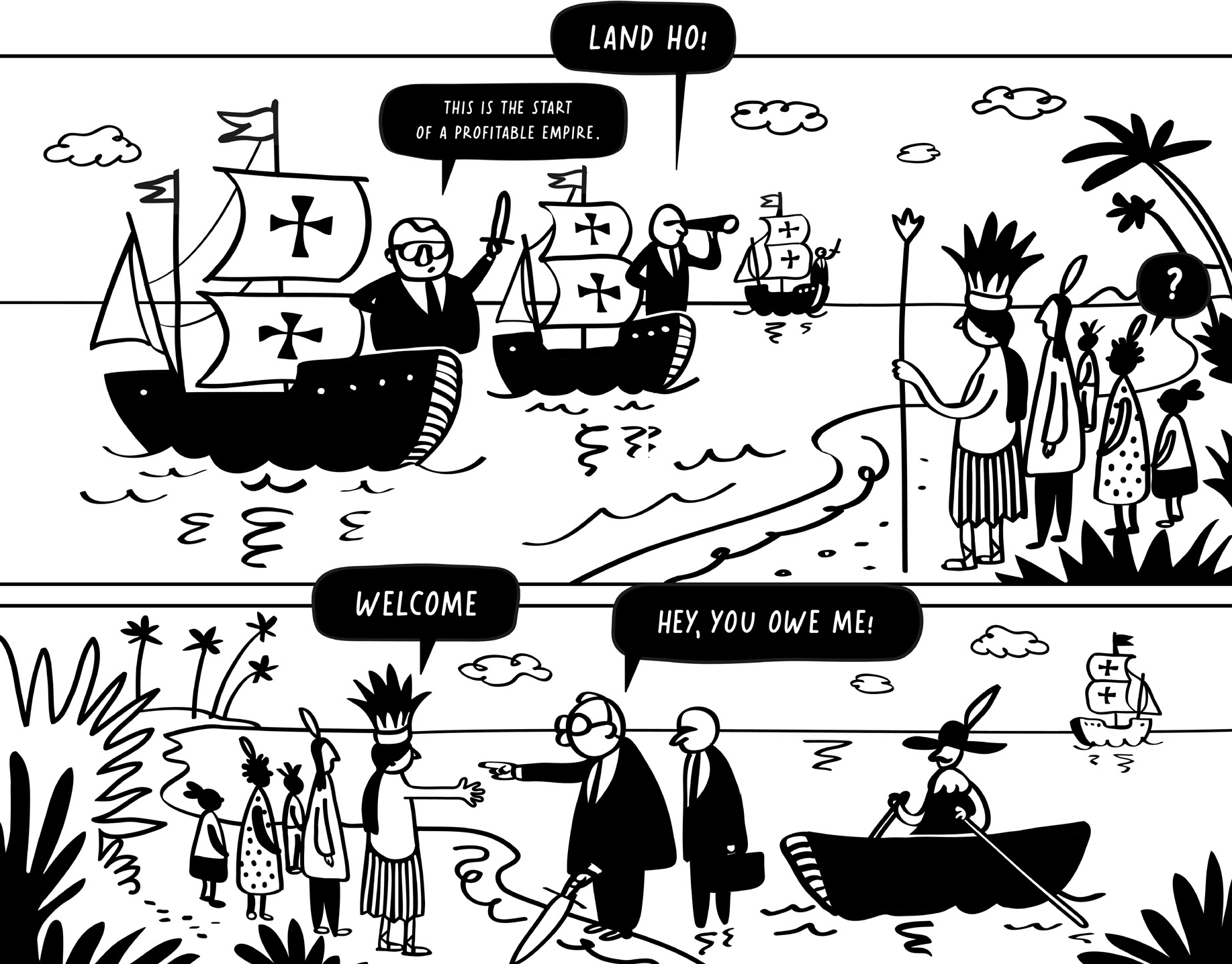

Origins of debt: Colonial and imperial legacies

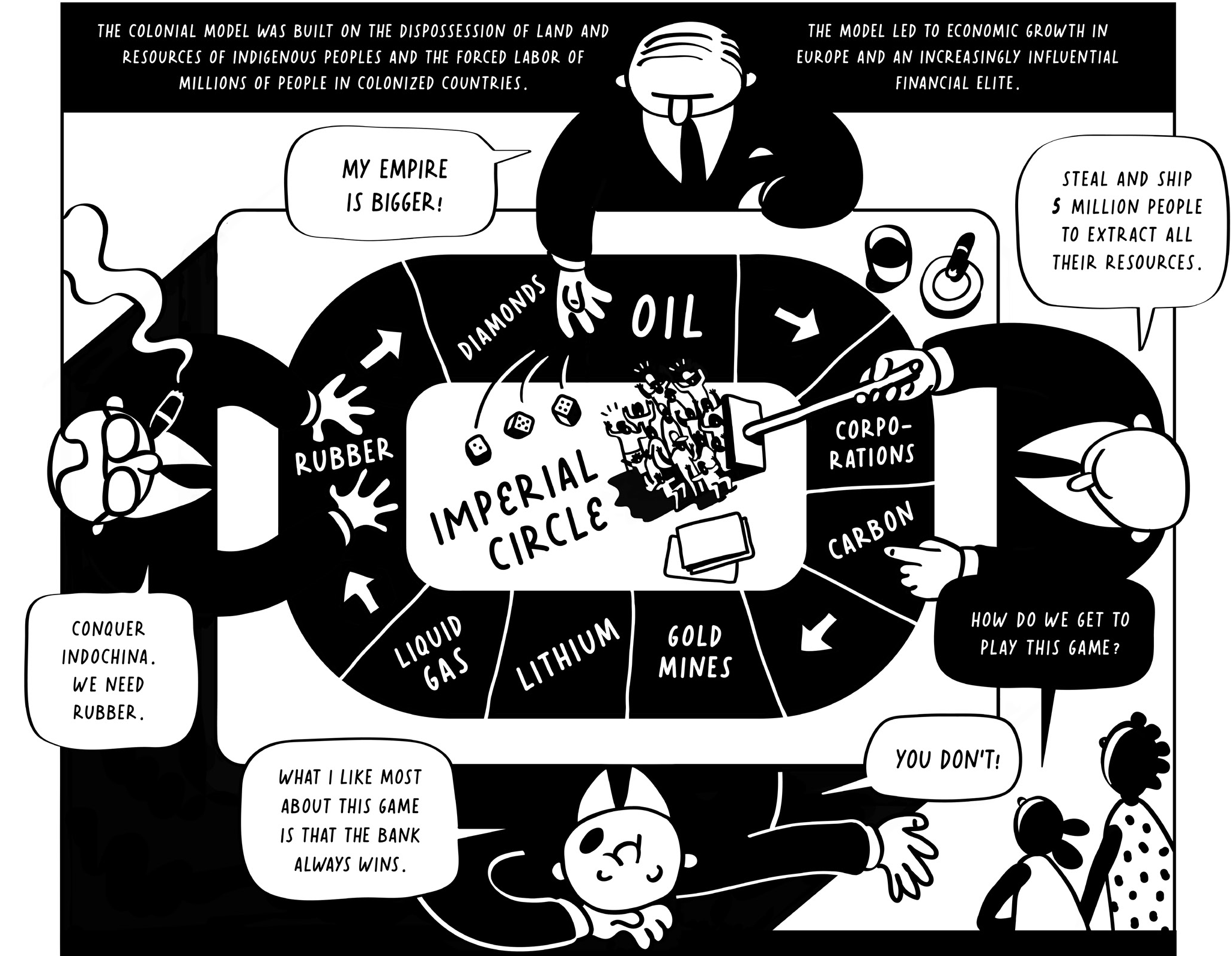

The global economy has experienced four waves of debt accumulation over the past fifty years since 1970. The first three ended with financial crises in many poor and wealthy countries: the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, and the global financial crisis of 2007-08. The current wave started in 2010 and reached an initial record high of $55 trillion in 2018. This latest crisis has led to the ballooning of debt in most economies, making it larger, faster, and more broad-based than in the previous three waves. These waves of debt and related crises are entrenched in colonialism, imperialism and financial capitalism orchestrated by wealthy countries, individuals and corporations to advance their neo-colonial extractions with the aid of International Financial Institutions (IFIs) like the IMF, the World Bank, private banks and a growing number of public development banks. In particular, the influence of financial corporate elites is manifested actively and passively through business, lobbying or networking and has a direct impact on the lending policies of the IMF and other financial institutions. In his remarks at the 1987 Summit of the Organization of African Union, Thomas Sankara – the former president of Burkina Faso, who was assassinated for trying to build alternative models of development, centering women’s rights and equality, and standing in solidarity with other anti-colonial and socialist struggles – proclaimed: “We think that debt has to be seen from the perspective of its origins. Debt originated from colonialism and imperialism. Those who lend us money are those who colonized us. They are the same ones who used to manage our states and economies.”

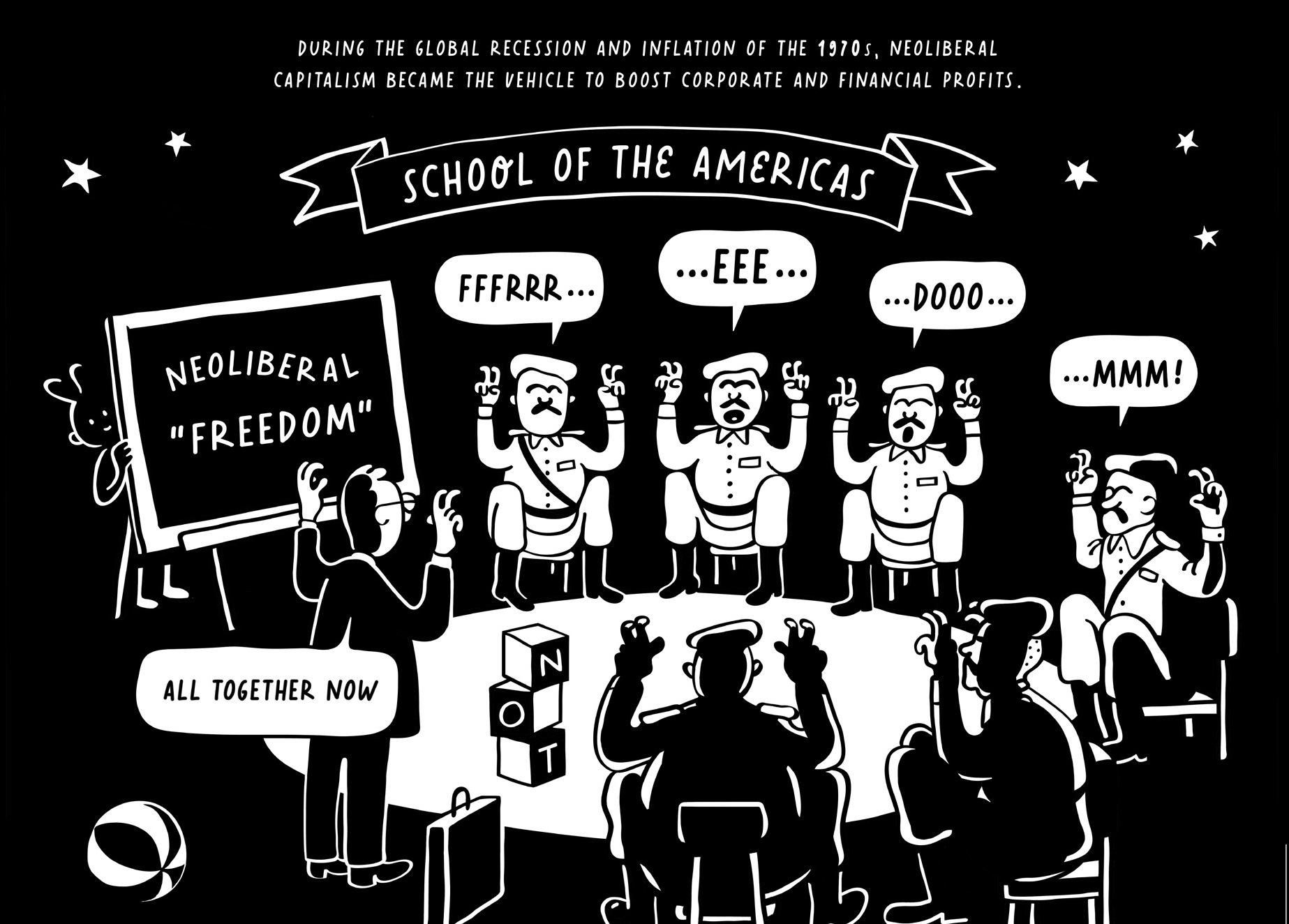

In the 1990s, following the fall of the USSR and the rise of the US as the world’s briefly unrivaled superpower, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the US Department of Treasury and the World Trade Organization adopted a set of economic policies which later became known as the Washington Consensus – a term coined by British economist John Williamson. These reforms ushered in neoliberalism as a political and economic philosophy that emphasized free trade, deregulation, globalization, privatization, paving the way for huge profits for the private sector. For instance, through the Washington Consensus the IMF has been able to impose measures that forced countries to shift public spending priorities away from essential services such as health and education, to liberalize trade, allow foreign investment, privatize state enterprises, strengthen private property, and reform tax regimes to benefit private actors and large investors. However, this economic model led to the destruction of prior institutional frameworks and powers, challenging traditional forms of state sovereignty, divisions of labour, social relations, welfare provisions, technological mixes, ways of life and thought, reproductive activities, attachments to the land and habits of the heart.

The Washington Consensus was enabled by structural conditions, including historic realignments in global political and economic power, and dominant ideas within academic economics. However, it is also the result of deliberate actions of powerful agents: the United States government, with the backing of the corporate world in alliance with other wealthy-country governments and like-minded officials in international organizations.

Under the unrivaled neoliberal hegemony of the US, debt has become an increasingly powerful tool of economic imperialism, reshaping economic policies and facilitating ongoing dispossession to the benefit of narrow private interests. The long history of debts imposed in many countries and colonialist policies that prevented these countries from entering global capital markets is not only unjust but also burdensome as these debts were virtually impossible to repay without taking on additional loans. If countries default, they are locked out of global capital markets and cannot buy basic necessities for their people. So countries turn to the IMF as the lender of last resort, but IMF loans come with neoliberal conditionalities, from Structural Adjustment Programs, Austerity, to Poverty Reduction Strategy Programs. Through these conditionalities, the IMF has forced countries, in concert with private and public debt holders, to prioritize debt repayment via privatization (i.e. selling off public goods and services), to cut public spending and pensions, regressive value-added taxes (VATs), labor market deregulation, and so on. In the case of Gabon, the IMF imposed austerity measures included a substantial cut in public spending and a reduction on fiscal deficit from 6.6% of the GDP in 2016 to 4.6 in 2017, significantly impacting the health sector’s ability to provide services. As a consequence, Gabon’s public health sector collapsed, public insurance schemes suffered, and citizens were left vulnerable and exposed to out of pocket spending which often sank families into poverty.

At Zimbabwe’s birth in 1980, the country inherited a $700 million debt from the Rhodesian Government of Ian Smith. The loans had been used to buy weapons in the 1970s, breaking UN sanctions. The UK gave ‘aid’ loans tied to Zimbabwe buying products from British corporations such as General Electric and Westinghouse. Spain lent money for military aircrafts made by corporations in Spain. The UK backed further loans for the Zimbabwean government to buy British made Hawk aircrafts – later used for the Second Congo War, which drew Zimbabwe and several other African countries into conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1998. In part, the new loans were taken out to pay the Rhodesian debts, fund post-war reconstruction, and cope with a large drought in the early 1980s. However, most of it ended up benefiting corporations from Spain and Britain at the expense of growing debt in Zimbabwe.

What is corporate capture?

ESCR-Net members have defined corporate capture as the means by which an economic elite undermines the realization of human rights and the environment by exerting influence over domestic and international decision-makers and public institutions. The elements of corporate capture identified by members include; community manipulation, economic diplomacy, judicial interference, legislative and policy influence, privatizing public security services, revolving door and shaping narratives.

- Countries

- Issues

- Resource Categories

- Resource Types

- Working Groups

- Members